In Country

Our guide Canh very kindly arranged for us to visit his home village and have lunch with his parents, sister, and brother-in-law. His father and mother appeared to be in their 80s. They greeted us with great kindness. His mother’s teeth were dead black from chewing betel nut, a mild stimulant that is a habit with many older women.

Explore villages

Canh’s young nephew was there, and after lunch, he and our three spent half an hour kicking a mostly-deflated soccer ball around the cement courtyard of Canh’s family’s house. The kick-around came to an end when Alec sustained his inevitable minor injury when he rushed in to kick his big brother in the ankles

Next, we all went for a walk through the village and out into the rice paddies. As we walked, we could hear announcements over the loudspeaker at Party headquarters. These announcements are a regular feature of daily life, sort of like political commercials in the U. S. in the weeks before a crucial primary. (Actually, exactly not like that. As a one-party nominally Communist state, Vietnam has nothing like America’s democratic, boisterous, and combative primaries.) These broadcasts can start as early as 5:30 a.m., and range from the practical to the ridiculous: Vaccinations this morning for all children from four to six. Everyone turns out to clean the streets. Or perhaps patriotic music or merely a local Party flunky reading the news.

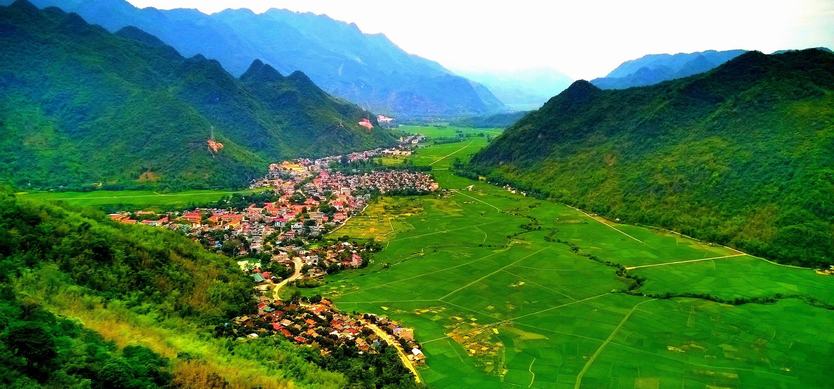

The rice paddies stretch around the village, occupying all of the ground not already filled by a building or road. Rice cultivation here is mostly manual, though we did see one old tractor.

Rice paddies in Mai Chau

Rice produces more grain per square meter of cultivated land than other crops, but it does so at the cost of a massive amount of backbreaking and painstaking work. The soil must first be leveled, then flooded, then fertilized, typically by scattering dried dung across the surface by hand. Once flooded and fertilized, the rice seedlings are planted by hand, a job that involves hours upon hours bent over, pushing tiny clusters of rice stalks into the underwater mud by hand. Some workers who can afford them wear high rubber boots. Others are barefoot. We saw a leech the size of my thumb in the water channel alongside a rice paddy yesterday.

A 360 square meter rice plot will grow two crops a year, each about 500 kg. The current market price for rice is 6,000 dong per kg (about 35 cents), so such a family-size plot would provide the income of less than $400 per year, with several family members working on it for hours each day. Growing vegetables can be somewhat more profitable, but timing is everything. Early eggplants may sell for $1.00 per kilo, but later on in the season, when everyone’s eggplants are producing, they may sell for only pennies. Realistically, this means people need a second job to make ends meet.

The government controls the land. If you are living and working in the village, you can keep your family’s assigned plot. If you go to the city and get a job, they will take your parcel away and give it to a different family. So the government gets much of the benefits of private agriculture, with each family having a direct incentive to produce, without giving up actual ownership or long-term control of the land. In the immediate post-war period, the government was into standard Communist brain-dead collective agriculture, and hunger was a major issue. In the 1980s, the state implemented the doi moi reforms (basically making individuals or families responsible for their production), and now Vietnam is the world’s second-largest rice exporter.

The next day

Our van met us on the other side of the village, and we headed off to our homestay in Mai Chau. On the way, we passed a green jewel of a golf course, positioned in a stunning setting between vertical white pillars of karst limestone. Our guide pointed to it. “This is being built by South Korean company.”

I was surprised. It had not occurred to me that South Koreans were peripatetic golfers like the Japanese. “So Koreans come here just to play golf?” I asked.

“No, it is not for Koreans. It is for the governors.” Meaning Vietnam’s party leaders. So in the “classless” worker’s paradise of Vietnam, the leadership cadres have taken up the most upper-class of sports. It is clear that the one-party state here has the same outcome as one-party states everywhere – the government becomes a mechanism to enrich and empower the leadership class, at the expense of both the liberties and economic advancement of the ordinary folks. The unconstrained power of the Socialist elite here would make Eliot Spitzer envious, and the opportunities for graft would impress even a Chicago Democrat.

When the country finally makes a transition to full capitalism and democracy, the leadership class and its offspring will already own and control most of what is worth owning. The road to Mai Chau passes through steep mountains on switchback roads. If we’d kept going for another six hours or so, we would have come to Dien Bien Phu, the valley where the French set up their airfield and hilltop fire-bases, intending to force a decisive engagement against the Viet Minh forces commanded by General Giap. They got their decisive battle, but the result was not what the French expected.

We stopped on the way for sugar cane, and a toilet break. “The bathroom is out back.” That “bathroom” was a cement trough the size of a large coffin, with human waste and newspaper (toilet paper substitute here in rural Vietnam) piled in along with agricultural waste and ordinary trash. Flies buzzed happily amid the dangerous debris. The boys and I took care of our thankfully limited bathroom requirements, then stood guard for the ladies. I was as usual in awe of the excellent temper shown by my wife, despite conditions that were challenging even for those of us of the pee-standing-up persuasion.

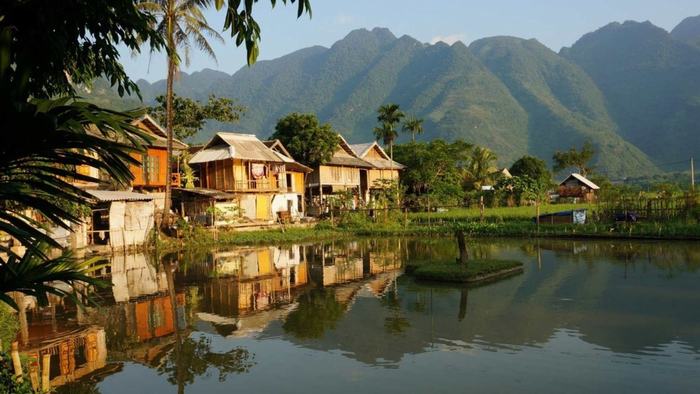

Homestay in Mai Chau

At our home-stay in Mai Chau, the whole family plus our guide slept together in a large second-floor room, on a bamboo floor covered with grain sacks. The house stands up on stilts, and space below is a combination dining room and fabric shop. Our hosts were an older Vietnamese couple with six daughters, the youngest of whom is about twenty and still at home.

Before dinner, we were invited to sit down with by the ancient woman who owns the house. She gave us a black-toothed smile (more betel nuts) and poured us each a large shot of rice vodka. She smiled at us and knocked her back.

I did the same. I’ve drunk worse things, though I’m not sure exactly when. Amy was less happy than me, but she bravely wrestled hers down. We politely declined refills. Our hostess left. As Amy recovered her breath, she commented to me, “Maybe it is good for you. She seems frisky. How old do you think she is, 80?”

I shook my head. “Amy, that chick is only twenty-six.”

The food here is delicious but very heavy on ex-pig, which none of the Hemphills eat but me. Leaving a large plate of food seems ungracious, so I’ve been eating way too much.

I suspect my snores sound like grunts at this point.

Before bedtime, our hosts strung big blue mosquito nets over our sleeping areas. Our beds were thin cotton mattresses on top of netting sacks on top of split bamboo. Most beds in Asia are on the stony side of firm, but these were the hardest yet. We did have nice comforters, so we were bruised but warm.

The next two days we took long walks through the hills and rice paddies, through Hmong and White Tai villages. The country here is striking with flat rice paddies in between near-vertical limestone mountains. Fighting in this country must have been a nightmare for French, Vietnamese and Americans alike.

During a walk in the hills, we came upon an open-air smithy. The blacksmith and his helper were fashioning farm tools out of scrap metal. Nearby was a big lozenge-shaped piece of iron, about four feet long, more than a foot in diameter, with a section of the half-inch-thick skin bent outward and partly cut off. It was a bomb from a B-52, apparently unexploded and with munitions removed, now brought here to be cut up and turned into farming implements.

Talk about your swords into plowshares.

For some time Amy has been asking me how I think the trip is changing me. I’ve always been at a loss for a substantive response. For the first time, I am noticing a real change in my head. Here in Vietnam, reminders of the war are common, and I often find myself identifying with the locals, and not with my fellow Americans.

On the way back to the village we passed two teenage boys in Manchester United and Arsenal football jerseys. (We tried to have a football-based conversation, but they had not English and did not appear to know the names of the players whose numbered uniforms they wore.)

Near our homestay, Katharine and I bought hand-embroidered shirts with wooden toggle fasteners instead of buttons. A men’s XXL was only 50,000 dong – about $3.50. It is cheaper to buy a new shirt here than to get a T-shirt washed in the typical international-chain hotel back in Hanoi.

Sizes here are way different from those in the U. S. Back home, I wear XXL t-shirts as pajama tops, and they are beautiful and loose. (That is my story, and I’m sticking to it.) Here an XXL is more than a bit snug, but at least it is clean.

On the road back to Hanoi, we passed a 100cc scooter with four riders: a man, his wife, and two dead pigs, one small and one enormous. Amy distracted Katharine and the boys. A pig roast in Baltimore put my daughter off meat, and one vegetarian in the family is more than enough.

For more information about Mai Chau biking tours, you can visit our website. If you have any questions, feel free to contact us. Have a nice trip!